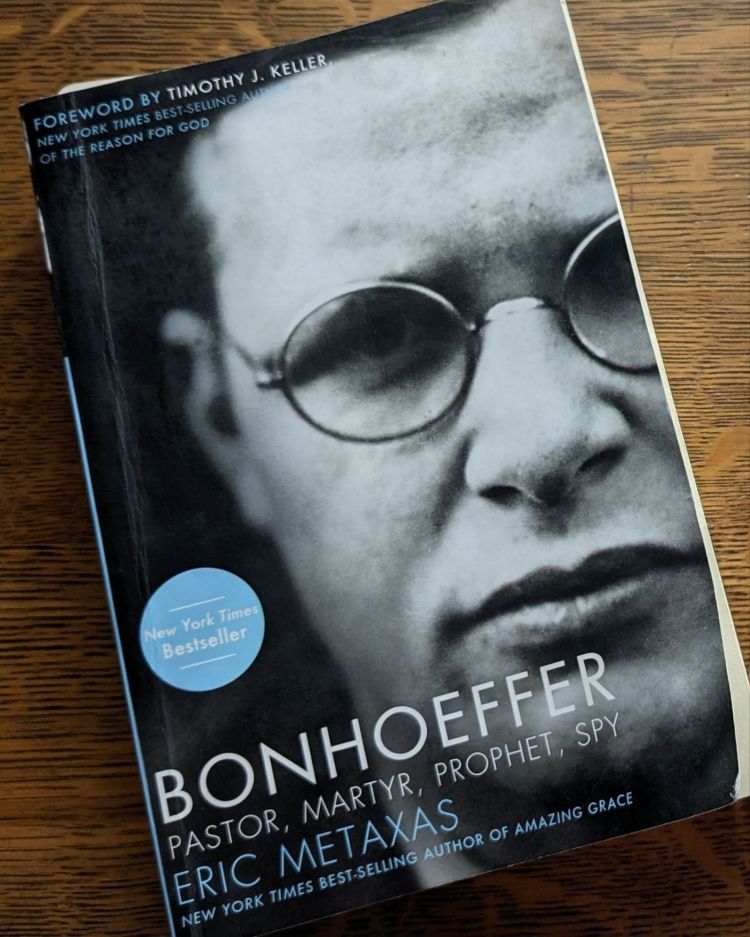

I gave this book 5 stars before I even finished it. I honestly don’t know how I can possibly write a review that will give it justice, without the review being so long that you might as well just read the book itself.

Here is the succinct review I left on Goodreads:

“An incredibly rich biography of a faithful and often misunderstood servant of God. The book is lengthy but Metaxas’ writing style allows it to move quickly, even with the depth of information.

“Readers outside the Christian faith may not appreciate the work, but those looking for a book that is both historically rich and spiritually nourishing will love the inspiration and encouragement contained within its pages. Messages which are as applicable to our time as they were to Bonhoeffer’s.”

I don’t mean to say that readers who do not share Bonhoeffer’s faith will not appreciate this book. Only that some reviewers commented that the book’s religious focus was too much for them. However, anyone who truly wants to get to know Bonhoeffer must take the time to read this book. I read it in less than 3 months–with plenty of other books going at the same time.

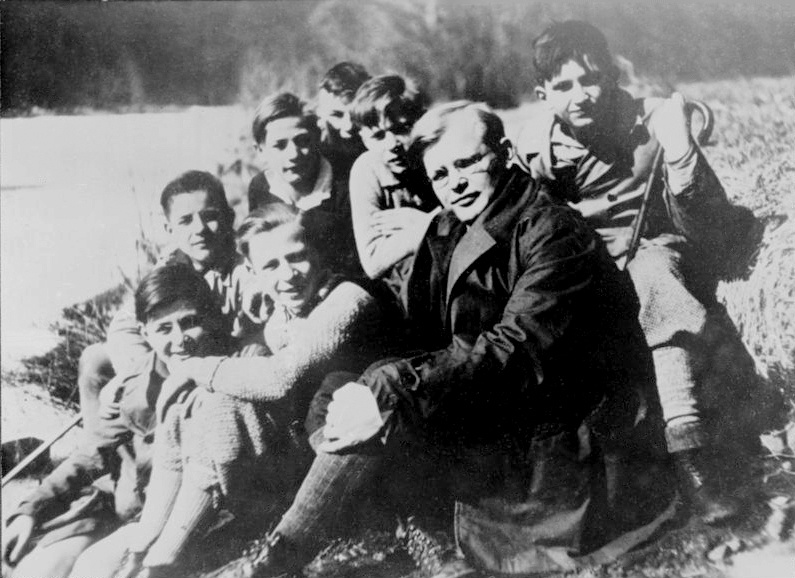

Author Eric Metaxas strives to give the reader background information about the constant changes in German politics and society throughout the book, as Bonhoeffer’s life spanned three eras: Imperial Germany, the Weimar Republic, and Nazi Germany. From the very beginning, the Bonhoeffer family was staunchly against the rise of the National Socialist German Workers Party (“Nazi” is just a shortening of the name of this political party). After gaining control of the government, the Nazis began to draw the German Church under their leadership as well. This was not something Bonhoeffer would tolerate, and therefore, the young pastor worked passionately to call the true church (which he called the “Confessing Church”) out of the larger German Church.

By Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R0211-316 / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5436013

Metaxas helps the reader understand the difference between the concept of “separation of church and state” as it is applied in Germany versus the way it is applied in the United States, and a great deal of time is devoted to describing Bonhoeffer’s struggle to build up the true church in the years before the Second World War.

For Bonhoeffer, the time came when he began to realize that he must change his tactics. His colleagues in the Confessing Church begin to wonder if he has sold out, gone over to the proverbial “dark side,” and become a Nazi supporter, but in truth, Bonhoeffer was picking his battles. He believed that making an issue of the wrong things would preclude him from being able to make a difference when it really mattered.

By Summer 1939, with war brewing in Europe, trusted friends advised Bonhoeffer to flee to America to avoid being drafted. He saw no other option himself, but when he arrived in the United States, he felt no peace. Though he wished to avoid being sent to the front, he felt he had abandoned his people:

“I have come to the conclusion that I have made a mistake in coming to America. I must live through this difficult period of our national history with the Christian people of Germany. I shall have no right to participate in the reconstruction of Christian life in Germany after the war if I do not share the trials of this time with my people.”

He would not be sent to the front upon his return to Germany. He would instead be drawn into the conspiracy that had been forming against Hitler for years. He would no longer simply provide prayer and spiritual support to those who were in a position to do something, he became an active player himself through a position with the German Abwehr (intelligence ministry). Here, he was able to maintain contact with church leaders and supporters in other parts of Europe, informing them of what was really going on in Germany. He was also able to work towards undermining the Nazi Gestapo and SD (organizations which were constantly in competition with the Abwehr).

In America, it is easy to assume that the German population knew about and supported (or at least, didn’t speak out against) the deportations of Jews and their eventual extermination. However, this information was not commonly known, and it was only because of the unique position of the Bonhoeffer family in German society that they were privy to such information early on.

Once Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, special units were formed under the SS, and sent behind the advancing armies to liquidate large groups of people. Though the Wehrmacht was ultimately complicit in some of these crimes, these atrocities horrified many of the German generals, and the book describes what these men went through as things unfolded. It prompted a renewed effort to find a way to get rid of Hitler, a sentiment which had existed among many of the highest ranking members of the German military for years. However, when they reached out to the Allies for help, they were rebuffed again and again. As Metaxas notes, Churchill and many other British leaders saw every German as a Nazi.

When they could not convince Hitler to stop the genocide, some of these officers resigned, were dismissed, or committed suicide. Metaxas points out that many of these men were God-fearing Christians, a tradition that was particularly strong amongst the Prussian aristocracy (Prussia being the former Northeastern part of Germany, which now belongs to Poland and Russia). It was families like these that supported Bonhoeffer’s earlier efforts to provide training to Confessing Church pastors during the early years of the Third Reich.

In view of Bonhoeffer’s increasing involvement with the conspiracy to assassinate Hitler, which required him to act secretly and even dishonestly at times, Metaxas goes into a discussion of Bonhoeffer’s willingness to be misunderstood. He says:

Bonhoeffer’s willingness to engage in deception stemmed not from a cavalier attitude toward the truth, but from a respect for the truth that was so deep, it forced him beyond the easy legalism of truth telling.

Bonhoeffer had an unusual ability to find the balance between faith and action, something that few Christians of any age are able to achieve. Whether or not one agrees with his decision, his viewpoint is worthy of consideration for anyone living in unprecedented times. His decision to become actively involved in an attempt on Hitler’s life came down to the idea that one must be willing to sin:

“…willing to unshackle themselves from the bonds of legalism, perhaps even to sin, in order to obey God.”

I sat with this for quite a while. God does not lead us into sin, but He also does not micromanage us. Because we are sinful people living in a sinful world, it is possible that we occasionally sin in the process of trying to carry out His will. We also must accept that our actions may be perceived as sin by others.

Yet this fear of sin may very well be what prevents us from doing the very thing we are being called to do. Bonhoeffer knew he was in a position to do something, and was urged by his sister in law, Emmi:

“You Christians are glad when someone else does what you know must be done, but it seems that somehow you are unwilling to get your own hands dirty and do it.”

Metaxas points out that she was not urging him to assassinate Hitler himself, but questioning why, if Bonhoeffer was in a position to do something, he wasn’t doing it.

Achtung! Personal Reflections Ahead:

In my own life, I have asked such questions on a lower level. Here is one example: because of the overwhelmingly conservative atmosphere of the American church, many of us have been brought up believing that going to a bar is bad, and that we might cause another brother or sister to stumble if they should see us entering or exiting such an establishment. It does not seem to matter that there may be people inside those places who are desperately in need of hope. Pastors and churches are keen to tell their congregants, “invite somebody to church,” but if we are honest with ourselves, we know that a lot of people out there would never set foot in a church. In light of that, shouldn’t we be willing to go where they are? It is so easy to want to cocoon ourselves where we feel it is safe, where we will not stumble or be stumbled, and yet, we have taken the light out of the very world that needs us most.

Spoken or unspoken, this theme has repeated itself in this and other books I have read recently (for example, Erwin Lutzer’s Hitler’s Cross). Perhaps not everyone would advocate for walking into a bar, and that is not my specific intent here (certainly there are those who should not because of a history of alcohol abuse), but the sentiment is this: as Christians recede from the world around them, we take the light away with us.

Furthermore, our goal in becoming involved in the world outside should not be simply for the sake of converting people. It should be to share our God-given gifts with the world around us, and not only those in our Christian circles! If it sounds like I’m preaching, forgive me. It is only because this is something I have had to learn myself. It is why I have begun to focus so much of my energy on activities outside of the church, and why I have started to stray away from purely Christian fiction and write to a broader audience (though my books maintain a Christian worldview).

This brings me to a key point in Bonhoeffer’s worldview that a lot of people have struggled with. He did not fit into either camp: the intellectual dogmatics of the Lutheran church, which viewed the Bible with head knowledge and little heart knowledge, or that of the pietists, who were keen to escape this world by living holy lives and eschewing anything worldly. In Bonhoeffer’s view, when one was fully surrendered to God, one could enjoy the things of the world in the way God had intended.

via Wikimedia Commons

I have only begun to delve into Bonhoeffer’s theology, but I think that understanding it is somewhat like understanding the Bible: one has to take it in the context of the whole, and not cherry pick a phrase here or there. As Metaxas points out, some of the things which are misunderstood as Bonhoeffer’s “doctrine” come from musings in his personal letters to his best friend, Eberhard Bethge. These were not things he ever intended to be published. Bonhoeffer was trying to sort things out in his mind, and using Bethge as a trusted “sounding board.”

As far as history is concerned, the SD and Gestapo eventually caught up with Bonhoeffer and the other members of the conspiracy. He was arrested and taken to Tegel Prison in Berlin where he was able to continue his work through friendly jailers. Eventually, this came to an end. His circumstances worsened. He was transferred to a prison at the Gestapo headquarters, but after an Allied air raid destroyed the site, he was taken to the SS Barracks at Buchenwald.

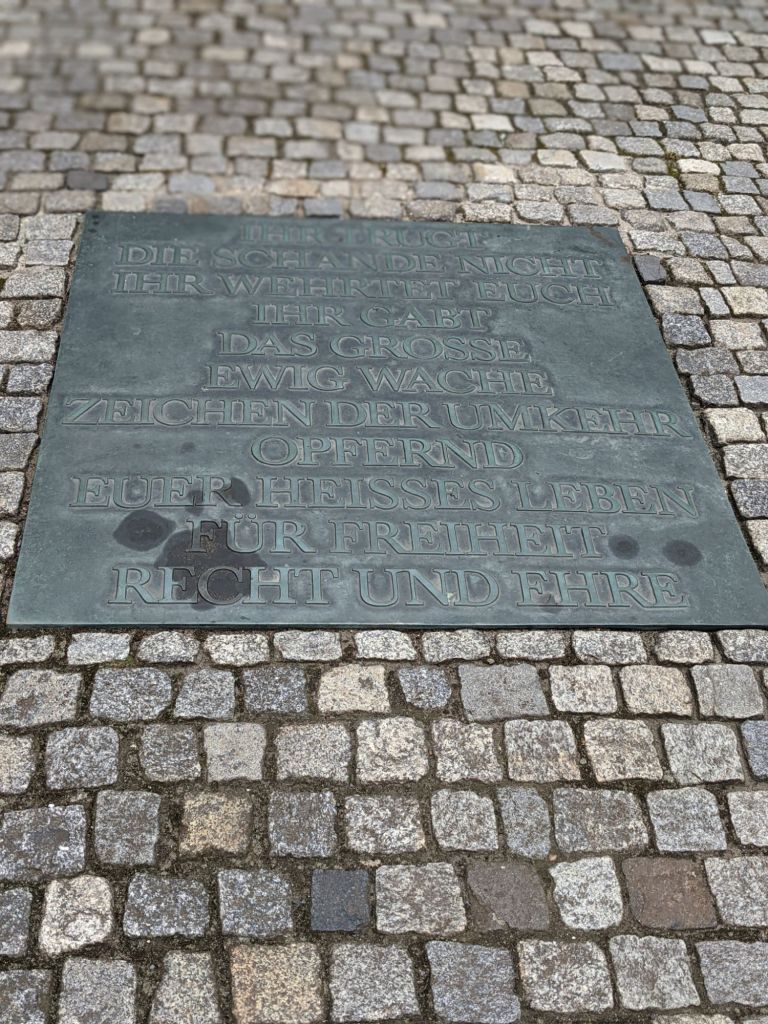

We visited the ruins of this site in 2022:

Metaxas’ account of the final days of Bonhoeffer’s life is not without a note of humor, refreshingly gleaned from the ill-fated journey from Buchenwald to Flossenbürg and the reunion with the families of other conspirators at the state prison in Regensburg.

His life came to an end on April 9th, 1945, and though it seems like a tragic and all-too-soon end to his remarkable life, I do not think Bonhoeffer viewed it this way. Even the story of his imprisonment is evidence that all along, God placed him exactly where he needed to be. Where he could be of the most use.

He died fully surrendered to the will of God.

I feel like there is so much more I could share, judging from the annotations and underlines in my copy of this book. It is an essential companion piece for anyone who has an interest in Bonhoeffer’s writings and life.

The book also lends itself well to the story of the German Resistance. Bonhoeffer was involved in the well-known July 20, 1944 plot to kill Hitler (also known as Valkyrie or the Stauffenberg plot). Though Bonhoeffer was not executed along with the major players in this conspiracy, I want to take a moment to share a few photos of the Memorial to the German Resistance in the courtyard of the Bendlerblock in Berlin. The names of those who were put to death here on July 20th, 1944 are in the fourth photo below.

General Oberst Ludwig Beck, General der Infanterie Friedrich Olbricht, Oberst Claus Graf von Stauffenberg, Oberst Albrecht Ritter Mertz von Quirnheim, Oberleutnant Werner von Haeften

Do you want to be informed about the latest on the Aubrey Taylor Books Blog? Posts happen between 1 and 3 times a month, and focus primarily on writing, German history, films, and books. We also love to introduce you to other authors in a broad range of genres, so drop your email below to stay up-to-date!

Metaxas’s book sounds like an incredible biography of an incredible man. Great review and insight, Aubrey!

LikeLike