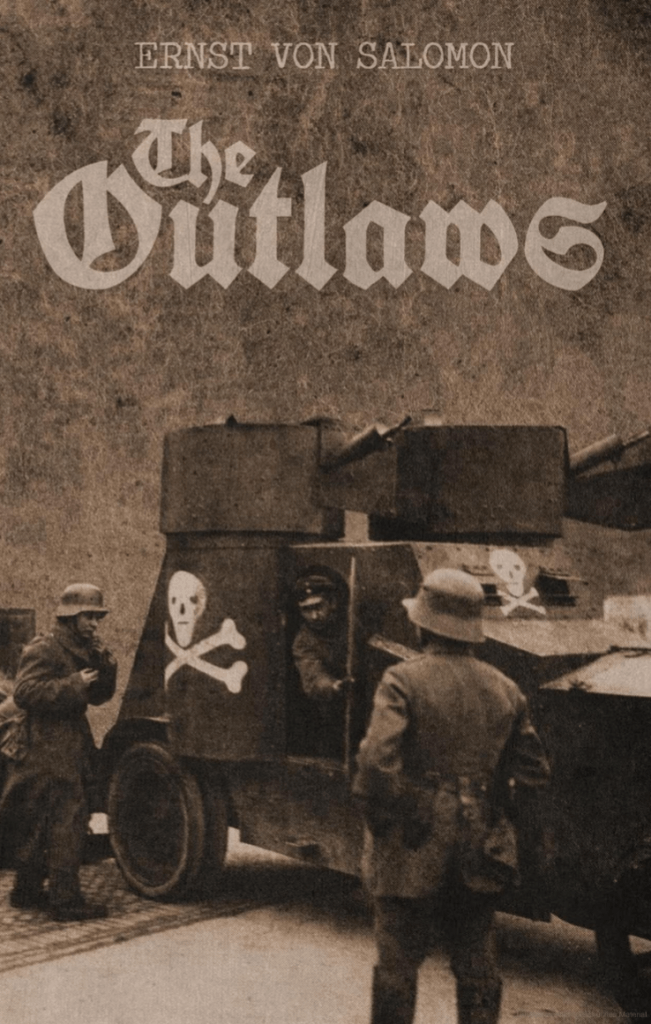

Ernst von Salomon’s book The Outlaws sat on my TBR for almost two years. It caught my attention as I was still contemplating what to do after I published my debut novel, Sani: The German Medic, and whether or not I was even going to continue writing. I thought it would be great for my research/background reading regarding the German Civil War and early Weimar Republic, but was ultimately put off in favor of other things.

As it turned out, the second book in my Gott Mit Uns Series did go back in time to Weimar, and did have characters that had been involved in the Freikorps (more on that in a moment), but those things were not the focal point. Rather, the focal point was Ernst Schmidt’s life after the Beer Hall Putsch, entwined with that of his son Jakob and his American cousin Friedrich. Ultimately, in Book 2 of my GMU Series, Jake Schmidt emerges as the main character, not Ernst.

But I digress.

Because I waited two and a half years to read The Outlaws, my knowledge base was quite a bit broader by the time I finally clicked PLAY on my Audible app. That knowledge helped me appreciate the book as someone who was already “in the know” and not as a novice discovering the patriotism, desperation, aimlessness and rebellion of the Freikorps for the first time.

Patriotism, desperation, aimlessness and rebellion. Those words really do describe the movement quite well. The German Freikorps were small bands of militia composed primarily of two types of men:

- fighting men who no longer found their place in normal society, yet had been ousted by the armistice from the only place they truly felt comfortable: in combat

- younger men who had been denied the honor of fighting for their nation, yet saw nothing in peacetime but financial ruin, shame, lack of prospects, and the increasingly corruption of Weimar society

“We realised fully what we were doing, we accepted the curse under which we had fallen—that violence breeds violence, and that we could not withdraw from our chosen path. Indeed, we felt a sense of duty in carrying out a historical purpose, which, while it relieved us of no personal responsibility, gave our actions an added excitement.”

Ernst von Salomon, The Outlaws

Whether you are interested in German history or not, the book lives up to its title. At times I felt as though were listening to a pirate story. At other times, a political thriller. Salomon and his comrades find peace nowhere, though they align from time to time with other groups that seem to share some common interest in the good of the German nation (this includes communists). Their true bane are those who “utter the word ‘Germany’ and mean ‘Europe’.”

“We are not fighting to make the nation happy—we are fighting to force it to tread in the path of its destiny.”

Ernst von Salomon, The Outlaws

There is some debate over how historical this book is and whether it is more of a memoir or a work of fiction. At the very least, Salomon was alive while all this was going on. Honestly, though, to write something like this, you have to have been involved in it. It is too vivid to be the product of someone’s imagination.

I felt like I was living the book all the way through, even when the audiobook narrator was less than fantastic. Perhaps Salomon was writing in Deep POV before Deep POV was even a thing. The book is written in first person, and although the main character never names himself, the reader can surmise that it is Salomon himself, who begins the tale (account) as a young military cadet at Lichterfelde towards the end of the First World War.

(For those who have read about Lichterfelde as an SS barracks, the Kaserne was built many years prior to the Third Reich and served as a Prussian military academy).

Salomon’s character was disillusioned watching defeated German soldiers march home. The end of the war only meant a fresh wave of political turmoil in Germany, such as the young nation had never seen (Germany only unified as a national entity in 1871). Further, they faced occupation by the Allied forces, particularly the Americans and their perpetual French enemies.

I have not researched this piece of propaganda specifically, but when I found it on Shutterstock, I noticed two things: first, the date (bottom right hand corner) is 1919, the year after the war ended. Second, the top line of the caption is translated, “German Men, protect your Homeland.”

A Schütze is simply a protector, and the verb schützen is to protect. There is a long history of militia in Germany, dating back to times when the protection of towns from marauders was left up to bands of armed citizens. With that in mind, perhaps it is not difficult to understand how this mindset would’ve been prevalent in the years after the First World War. What the Allies saw as just consequences, they saw as an unprovoked occupation.

However, the threat seen by the Freikorps extended far beyond German borders, where ethnic Germans had lived in other lands for hundreds of years. Salomon and his comrades found themselves engaged as far away as the Baltic States and Poland, first with and then without the approval of the German government.

The Outlaws is a fantastic study in the history of Germany from 1918 through 1927. Even if Salomon’s accounts are somewhat fictionalized, he follows the path of history closely: this is what many young men experienced. I appreciate the fact that at the beginning of some chapters, Salomon briefs the reader on the historical background of the events that will play it in that chapter. It is almost like he is saying, “Here’s what happened, and here’s the part I played in it.”

Ernst von Salomon was a clever writer and I enjoyed his dry wit. I also appreciated that, with one or two exceptions (one in particular, during his prison stay), there was no need for sexual content. Naturally, there was a lot of violence, given the subject matter, and some light cursing. Suspense, camaraderie, and German culture were all present, and even the lengthy account of his years in prison was fascinating, and not without humor.

This is important history for anyone who wants to understand that the Third Reich didn’t happen in a vacuum. Some even call the Freikorps “the vanguard of Nazism” (I believe there is a book by that title which, if I continue to develop one of my new characters, I may end up reading at some point). But there is a reason for even that. As an American high schooler, I was told conceptually that the First World War and the devastation of the German economy led to the rise of Hitler and the Second World War. A book like this helps the reader experience what many young men experienced at the time. Taken in entirety with the other things that were going on during the period (for example, on the home front, in politics, and in the arts and culture), it gives a much more complete picture of Weimar Germany: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this review and reflection on The Outlaws. Next week, I will be spotlighting a fellow Brave Author, Chevron Ross, who has recently released his latest novel, The Samaritan’s Patient. To stay informed on new blog posts, be sure to subscribe below.

Fantastic review, Aubrey! The Outlaws sounds like an awesome read.

LikeLike