***Spoiler Alerts***

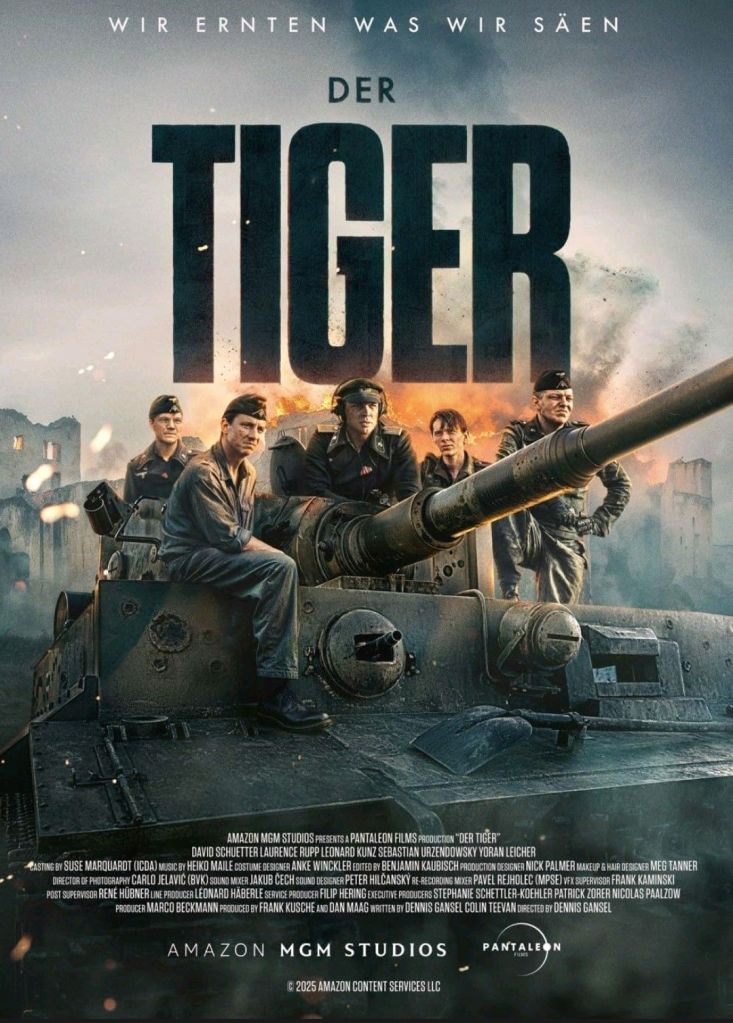

This movie is so deep and layered, so I’m not claiming to have it all “correct.” It received a lot of GREAT responses, but some harsh criticism as well, particularly regarding the ending. It is a tough film to interpret and the timeline is confusing, so I’m going to give my gut reaction, my understanding and interpretation of the film, and my takeaways. That’s what this blog series is for, anyway.

First and foremost, I was blown away by the acting in this film. Whoa. From the minefield to the underwater scenes, I felt like I was in the tank with the crew. (Who knew Tigers could go underwater? Not this amateur historian!)

I am a sucker for good characters, and when I read memoirs and histories of tank crews, this is what I picture: four or five distinct personalities, crammed into a tiny, dark, sweaty, stinky metal box, under the stress of battle and the fatigue of endless hours on the march–camaraderie at its finest, with the good, the bad, and the ugly.

One of the crew members even calls tank driver Helmut ugly but frankly, Helmut was my favorite. 100% my type of character. Someone should write fan fiction about him. But I digress…

I want to get the Pervitin thing out of the way up front. It is unfortunate that that is largely a premise of this film, according to the description on IMDb.

Yes, the Germans used it, and maybe the whole thing was a Pervitin-induced nightmare… but judging from the number of marijuana dispensaries there are in my city, and people’s reliance on substances and distractions to get through life, I don’t think modern society is in a position to judge the German soldier’s reliance on Pervitin. We’re not even in a war zone. (I know, that was harsh…)

This film is largely speculative, even if lead character, tank commander Leutnant Philip Gerkens is living a drug-induced hallucination… and it goes deeper than that anyway.

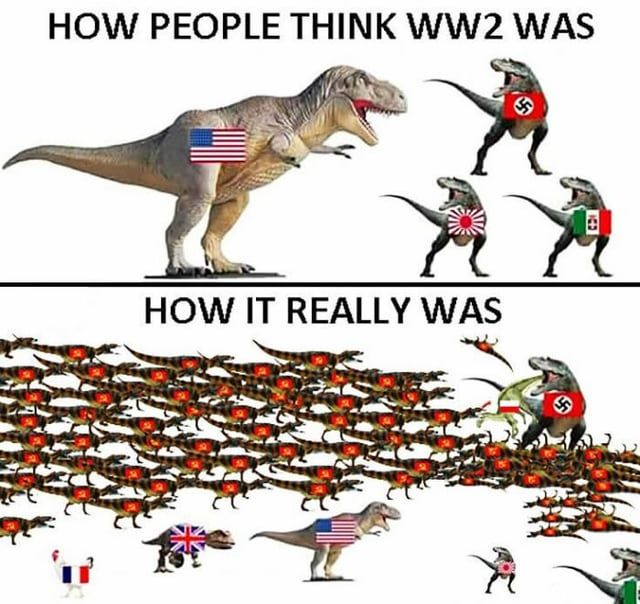

This film takes place on the Eastern Front. The war in Russia wasn’t just a cliché à la Hogans Heroes. It was incomprehensibly brutal, and the brutality was not simply a Soviet reaction to the German invasion. The Communist regime had been systematically killing their own people for two decades before the Germans arrived.

Soapbox moment: people with a casual interest in WWII, who are generally knowledgeable about the war in Europe, should read up on the Eastern Front, because until one understands the war in Russia, one cannot truly understand WWII.

Another thing that probably makes this film difficult for some viewers is that Der Tiger is a German film, and, in spite of the fact that MGM/Amazon had a hand in its production, it comes from the German heart. It is from their perspective, and if you have not experienced the memory of the war the way Germans do, this movie is going to hit very differently.

I say that as if I’m German, which I’m not. I am of German descent, and the closest I can come to their experience is having immersed myself, for five years now, in striving to understand their side of the story, not just with my brain but with my heart, and growing close to those who lived through it as children or teens. For me, Der Tiger hits about as well as it can someone who did not grow up with war guilt hanging over my head (although I knew instinctively, without ever being told, that the Allies bear their share of guilt and we just don’t talk about it).

I hope that aspect is not entirely lost on American viewers, in fact, I hope it makes them think. A lot. Otherwise, the film might as well have been released around Halloween, because on surface level, it makes a great ghost story (and certainly, some commenters have called it that).

It is fair enough to say that any viewer who goes into it thinking they are getting a war movie is going to get something different. The timeline is confusing, and I guess I understand that some viewers feel cheated when they realize that the whole thing was just a dream or hallucination anyway.

I am going to summarize the majority of the film here, but feel free to skip this section, especially if you’ve already seen the movie or have ADHD like I do.

In brief, the movie opens with the crew of a Tiger (a large German tank) breaking out of Stalingrad. The driver guns it across a kilometers-long bridge that is set to be blown up at midnight. Miraculously, they make it.

Suddenly, tank commander Philip is in a transport lorry (sorry, so used to reading British-translated German stuff) having been handed a special mission: Operation Labyrinth. His tank crew has been specially selected for the job.

They are to find and rescue a high-ranking officer, Paul von Hardenburg, from a secret bunker hidden deep in the woods. Hardenburg happens to be an old friend of Philip–and the godfather of Philip’s son.

Throughout the journey, we see hints and flashbacks of what is going on in Philip’s mind, but the mission makes no sense whatsoever to the crew, in fact one of the members eventually calls him on it and suggests that he be removed from command. (Felt like Star Trek for a brief second.) Philip continues to insist on following orders, even as things grow eerie and it becomes apparent that something isn’t right.

Philip and crew stumble upon an SS anti-partisan operation deep in the woods in which an entire village is being burned to the ground, women and children included. The SS officer in charge asks Paul, “You remember that fire, don’t you?”

At the time, the viewer is asking, “What fire?” We learn that Philip’s wife and child were killed in the Allied firebombing of Hamburg, but that is not the fire the SS officer is referring to. The fire he is referring to happened in Stalingrad, when Philip, again under orders, had his crew fire upon a building that was thought to hold partisans, but was also full of women and children.

Here, we begin to see the significance of the film’s tagline: you reap what you sow.

Since the end of WWII, one of the arguments about German war guilt has been just how culpable individual soldiers and officers were in atrocities and war crimes when they were just following orders. So it is with Philip. His actions in Stalingrad haunt him.

That piece does not become evident until close to the end of the film, which I do think creates confusion. We also learn that chronologically, Philip had been informed about his wife and child prior to blowing up the building in Stalingrad. How much does that affect his state of mind? Viewers don’t realize that he is reminiscing about his late wife and child as he is daydreaming from the commander’s hatch of the tank.

Finally, at least according to my interpretation, we learn that the crew of the tiger did not miraculously make it over the bridge. My husband was not the only viewer who expressed confusion about this: the great majority of the film takes place in a dream (hallucination?). At least, that’s what I think. Philip and his crew carried their guilt with them as they fell to their death, and the film just ends.

The ending did shock me, but I wasn’t unprepared: most German war films do not have happy endings. (That is also why I don’t feel it’s necessary to give my books happy endings.)

The Pervitin thing may be front and center in the “blurb” but honestly, there are only a couple of scenes and I think casual viewers won’t necessarily put two and two together. There is no sign that says “Philip had this nightmare because of Pervitin” and therefore, it is up to interpretation. Was it Pervitin or was it his own guilt? Was it both?

To me, Leutnant Philip Gerkens is an incredible and human character, even if he has not quite come to terms with his actions at Stalingrad and is being haunted by them. I love him as a leader, especially the way he handles Michel, the youngest man of his crew, in the minefield scene *chills.*

This was one of those movies that I was still thinking about when I woke up. It even bore its way into my devotional reading this morning.

***In closing, some thoughts stemming from a more “religious” worldview***

The theme of my devotional this morning was about how, when one throws a stone into a still body of water, it creates a ripple effect. Then, the author talked about how a second stone can change the manifestation of ripples entirely, preventing many of the original ripples from ever meeting the shore.

The first stone is our sin. The second is Christ. How greatly the ripple effects of our (individual) sins have been changed by His grace, mitigating the effects of sin across the world. Changing the story.

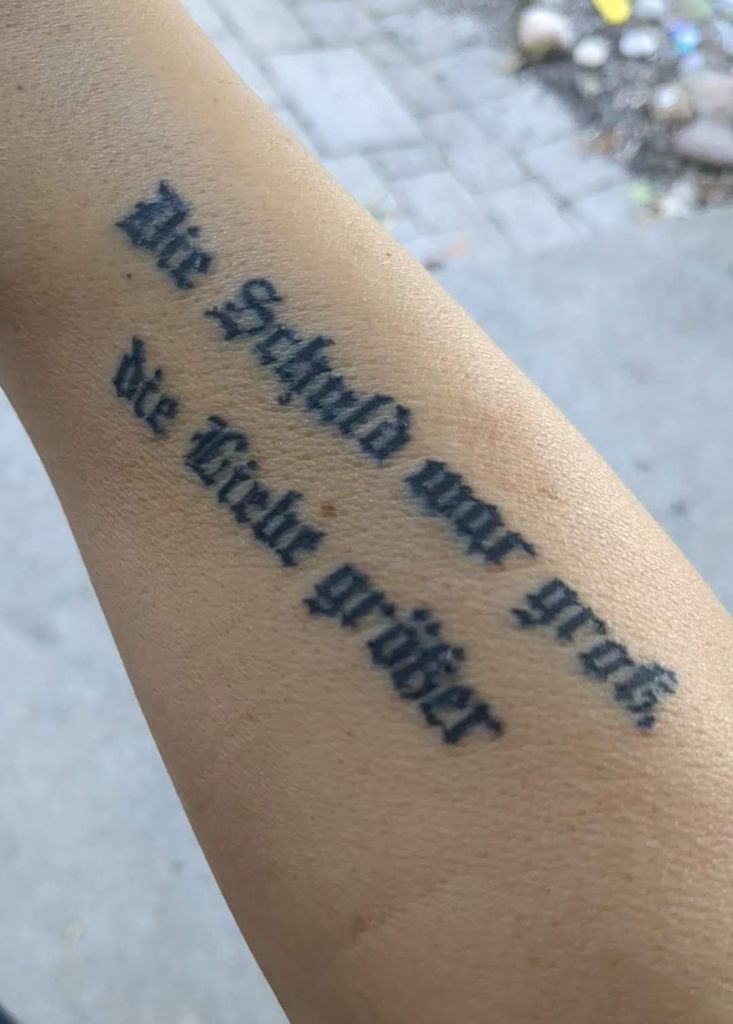

It was good for me to read that and contrast it with the hopeless, damning vision I saw last night. This sentiment is the inspiration behind the permanent ink on my arm, there for all to see: Die Schuld war groß, die Liebe größer.

I don’t expect all my readers to take an interest in or agree with this part of my post, but I can’t help but think about these things when I watch movies like this. There are plenty of people who still believe that Germans should be carrying around national guilt. It is true: we reap what we sow… BUT God.

No one needs to live under the shadow of their ancestor’s guilt and truly, it is not for us to make assumptions about the guilt of anyone. We don’t know the whole story.

If you want to be informed about the latest on the Aubrey Taylor Books Blog, sign up below. Posts happen between 1 and 3 times a month, and focus primarily on writing, German history and travel, as well as films and books. I will also introduce you to other authors in a variety of genres, so drop your email to stay up-to-date!

One thought on “Film Review and Reflections: Der Tiger aka. “The Tank””