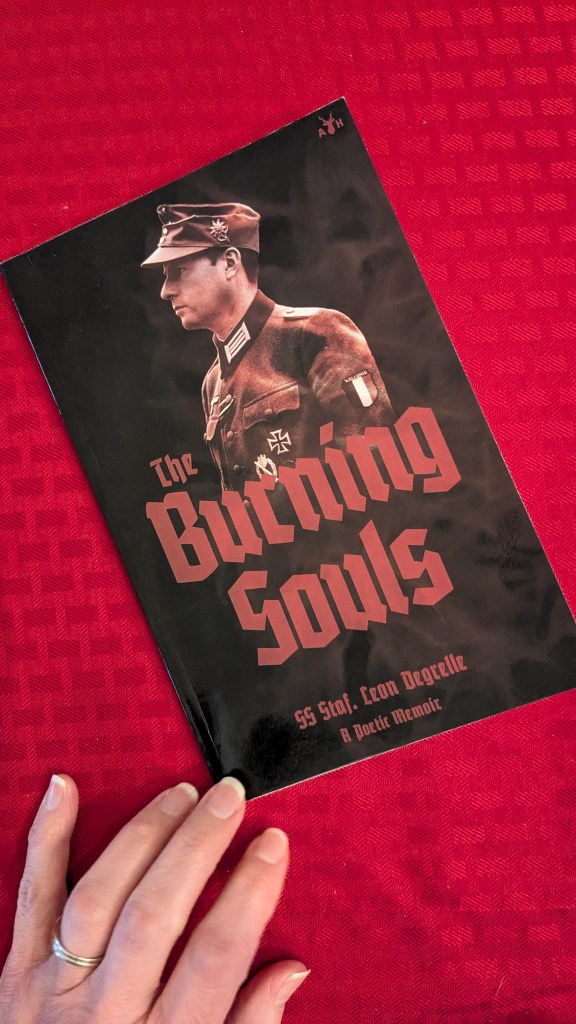

I knew the basics of Léon Degrelle’s story: the young, idealistic journalist-turned-leader of the Belgian Rexist party who has gone down in history as a Nazi-sympathizer and an unrepentant supporter of the National Socialist regime. He was not truly a fascist, but a populist, conservative, pro-family, pro-Church, devout Catholic who rejected liberalism and especially communism.

After the German invasion of Soviet Russia, Degrelle joined a Wallonian (French-speaking, southern Belgian) brigade of the German armed forces and fought for four years alongside the German divisions. He led his men through to the very end of the war, and escaped with his life to spend 50 years in exile in Spain.

Léon Degrelle can hardly be called a Nazi, but because of his support of the German regime, and friendly relationship with Hitler, he has been labeled as such. Certainly, his viewpoints “rub” against the accepted narrative, and there are a few passages in this book that show a demeaning opinion of certain people groups (primarily Mongols) — yet he readily confesses that it was the Germans’ advanced culture and need for comfort that led to their initial defeat in Russia.

Degrelle is not afraid to point fingers. He says, “After the defeat, the world worked unceasingly to mock the vanquished… Nothing was respected, neither the honor of the warrior, nor our parents, nor our homes.”

In light of this, upholding the honor and bravery of his men, and the righteousness of their cause, is of utmost concern throughout the book. Degrelle even questions whether one day people will regret the defeat of 1945. When I look at the growing chaos in Europe today, I can’t help but wonder if he was on to something. I’m not suggesting that fascism was right, but the turmoil, division, and destruction of culture is unmistakable, and inextricably linked to decisions made over the course of many years:

“…they were right in a negative sense, because Bolshevism is the end of all values… a united Europe, for which they strove, was the only–perhaps the last–possibility of survival for a marvelous old continent, a haven of human joy and fervor, but mangled and mutilated to the point of death.”

Of course, it is not Bolshevism we are dealing with today, but I’ve been in Germany four times in seven years. The Germany I visited at the end of 2024 was not the same Germany I fell in love with in 2017. To what do we owe this sad and drastic change? The politicians continue to debate–and hatred continues to grow.

At the end of his Preface, Degrelle says, “You, reader, friend or enemy–watch [my men] come back to life; for we are living in a period when one must look very hard to find real men, and they were that, to the very marrow of their bones as you will see.” Throughout the book, I found myself pondering that very question, as if repeating the opening line of “Holding Out for a Hero” by Bonnie Tyler. “Where have all the good men gone?”

It was not until 1941 that Léon Degrelle found himself in active support of the German policy. It was not something he chose on a whim, or overnight. He was one of hundreds of thousands of young men from all over Europe who perceived good in the German cause, in spite of (or perhaps as a result of) the German invasion of his homeland.

Many Belgians feared the very real threat of communism, a threat that even American General Patton saw in the days after the war ended. That realization has been immortalized in this statement: “We killed the wrong beast.”

Hundreds of thousands of young men joined European brigades of the Waffen-SS (which just means Armed SS). Belgium had two: the Wallonie, and the Flemish division (Langemarck).

Blucky190, escutcheon shape designed by Skjoldbro, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Léon Degrelle’s account is hands-down the most vivid and gripping depiction of WWII on the Eastern Front that I have ever read. Certainly, Guy Sajer’s The Forgotten Soldier ranks up there and deserves a second read-through. Like Sajer, Degrelle was an outsider, and he observes the Germans as an outsider would, often commenting on their orderliness and devotion to procedure, even in the worst of circumstances.

What is unique about Degrelle’s experience is that he rose from the position of a foot soldier to the SS-equivalent of Colonel (yes, I meant Colonel, not Corporal). The reader experiences his life at the front AND at the command post. They experience everything from his interactions with fellow soldiers to his interactions with generals, to his interactions with SS chief Heinrich Himmler and with Adolf Hitler himself.

Alber, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It is Degrelle’s passion and his keen eye for beauty that makes this memoir stand out. Along with mud, tension, gore, and fast-moving action, he takes time to observe and describe the beauty of flowers, forests, sunrises, glistening snow, and cathedrals. And he reflects on the meaning of it all.

Consider that this is in translation. It would have been yet more moving in his original French tongue:

“I went out by way of the garden. Beneath me the city was like an immense ship in flames. The ancient square towers of the medieval churches stood out dark and straight above the gigantic torches. They held out in the hurricane as though wanting to send up one more appeal toward the sky from the civilized centuries that were dying in the fire.

“They were pathetic, black against a red and gold background. never had they been so beautiful. never had they borne such solemn testimony. Poor towers of Stargard, blackened masts of the burning ship that for five hundred years had flown the noble flag of Christian Europe.

“This Europe that was being burned alive was the country of every one of us. These austere towers of the East were sisters to the great gray towers of Saint-Rombaut of Malines and the belfry of Bruges. All our countries of Europe answered to one another, as did the clock towers. I could hear the great dirge of these disasters resounding in my heart. And I couldn’t keep myself from crying…”

This was written very late in the war, February 16, 1945. He and his men were embroiled in the battle for Stargard, against the massive Russian army. He weeps for all of Europe, for many hundreds of years of Christian civilization.

Twenty years earlier, Russian churches had been shuttered and religion completely outlawed in places that fell under Soviet control. This was what many Europeans feared, along with the economic conditions that were being forced on the Russian peoples. That is to say nothing of the mass slaughters that had taken place during the Communist Revolution.

During the first few years of war in the East, conditions were as the Germans had expected them to be. Time and again, Degrelle refers to poor, destitute families living in deplorable conditions, children sleeping in squalor and adults who hated communism.

Many of these same peasants would eventually be swept up by the Russian army, given guns and forced to shoot at the Germans.

The Wallonie Legion was known as a unit that would rise to the occasion, do their duty and see it through to the end. More than once, they held out, served as rear guards, and protected other units in retreat. Yet the men of the Wallonie and other non-German units of the Waffen-SS had nothing to gain. Degrelle says of “his boys” who died in the Baltic campaign in 1944:

“Back there, at the far end of the Baltic countries, our dead remained, to bear eternal witness that in the tragic, life-and-death struggle for Europe, the sons of our people had done their duty, asking nothing and expecting nothing.

“We had no land to win, no material interest to assure back there. We were misunderstood by may, but resolute and happy. We knew that a pure and burning ideal is a marvelous good, for which a young man with a strong heart should know how to yearn, to struggle, and to die.”

After years of struggle in Russia, the Wallonie is sent home to Belgium. Degrelle expresses joy at being at home but his heart is wrenched when he sees how those who believed in their cause are being treated by the Allies and other Belgians who do not share their beliefs.

Even after four years of research and soaking in the German viewpoint, it was odd to come across Degrelle’s words: “The great dream of liberating the West crumbled.” We in America hold very strictly to the idea that we were the liberators. Many Europeans did see us that way, but many did not, and most of the latter have remained silent ever since.

In part, I suppose it depends on whether the “liberated people” were more concerned with fascism or communism. Herein is the value of being willing to read deeply and objectively into the other side of the story. To understand that many Germans and German-supporters saw the goals of both the communist East and the liberal West as vices.

In a few places, Degrelle openly indicts the British and Americans. He was aware that the US was sending armaments to Russia long before the US actually entered the war, and condemns the relentless Anglo-American bombing of civilians and towns.

“It had been proven that any effort to cut off the Soviet forces would be in vain. [They] were ten times stronger than we in men, and especially in equipment. Henceforth, barring the use at the very last minute of a super-weapon, the Soviets and their American backers were victorious.”

“Their bombs turned [La Roche] into a monstrous heap of ruins, with mounds of dead civilians beneath them. The Ardennes was flattened in a few days. not a town on a road to somewhere else, not a crossroads escaped. It was a terrible way to wage war, at the expense of women and children crushed in their cellars. But this means, which the Anglo-Americans used without any restraint, quickly proved to be decisive. At the end of a week all roads used by the columns of the Reich had become almost impassible.”

Late in the book, Degrelle describes the terrible flood of German refugees that was constantly getting in the way of the army’s attempts at communication and defense of the Reich. These hundreds of thousands of desperate civilians were bungled up with military traffic, and under constant attack from the Russians on the ground and the British in the air.

“A human river descending from Waren gathered momentum as it fled the Soviet tanks. Another…poured down from the Elbe… The British planes would dive onto the columns, and instantly ten or fifteen clouds of thick smoke would rise from them.”

Throughout the book, with every terrifying scene or battle he describes, things only seem to get worse a few pages later. For the Germans, it was often the nature of the war from 1942 on. It is extremely sobering to read memoirs that bring you to the very last days of the war in Europe: “Only those who lived through those frightful weeks at the end of the war in the East can imagine the butchery that took place.”

But it is not all bad. Degrelle has moments of levity and humor. He was enamored with the German soldiers he served alongside. When speaking of a waiting period on the Tuapse road, he describes the way the German soldiers would construct little wooden bungalows for themselves:

“Veritable forest cities sprang up. Every German has in his soul a mountain chalet. Some of these little buildings were masterpieces of grace, comfort, and solidity. Each one had a name. The most insignificant was entitled, with good humor, ‘House of German Art.'”

Degrelle also cared very much about the well-being of his men. When he had opportunity, he looked only for volunteers, knowing those were the men he could count on. He did not force men into a task if their hearts were not in it.

“They came to the Legion as volunteers… I wasn’t going to accept their blood unless it was offered freely.”

“At no price would I have wanted to send decent fellows into the fray, or even keep them in uniform, if they didn’t share our beliefs and hadn’t come of their own free will.”

You see the man’s heart. You also see the heart of his men:

“They believed in the immortality of their ideal. They wanted to obey right up to the end, to be faithful to the end–and the last fighters, if necessary, on ground that wasn’t even theirs.”

I can’t help but think that their loyalty had something to do with confidence and pride in their commanding officer.

There is always talk about the Nazis and their supporters fleeing Europe at the end of the war. In spite of whatever political accusations one might make about Léon Degrelle, I found myself thankful that his account, and his life, were preserved. To read his writing is to get to know him as a person, a man who was willing to give his life for his ideals, only to survive and be cut off from everything he knew and loved. He remained passionate, idealistic, and full of faith in God to the end.

The Eastern Front ends with Degrelle’s flight out of Norway to Spain, running so low on fuel that the pilot had to shift the plane side to side, and even straight down, to get the last vapors of fuel into the engines. They crash-landed on the coast of San Sebastian in Spain.

It remains to be seen if Léon Degrelle’s dreams come true. Will the people of Belgium see justice in the cause of the Belgian men who fought for the Germans? Will the world see any justice in the German cause itself?

I constantly ask myself these types of questions. I never planned on researching WWII from the German side, much less in order to write about it. Like most Americans, I was content to go on celebrating and believing in our cause, and in the narrative as it stands.

The trouble is, if there is something that just won’t leave you alone, you have to dig until you are satisfied. Unfortunately, the more you dig, the more you discover things that make you want to dig more. I’ve uncovered a lot that breaks my heart, and a lot that frustrates me because History has already been written, and the only One Who ultimately knows the truth is God. He was there; He saw everything on all sides. Yet it is with Him that the greatest comfort exists:

“For everything that is hidden will eventually be brought into the open, and every secret will be brought to light.” Mark 4:22, NLT

It’s not my job to prove or disprove anything, nor is it my job to defend or indict anyone for the purpose of changing people’s minds. Readers can easily disregard whatever I’ve said and keep their own opinions, or form new ones. I would only ask that they be willing to do the reading for themselves.

History weighs the merits of men.

LÉon Degrelle

If you want to be informed about the latest on the Aubrey Taylor Books Blog, sign up below. Posts happen between 1 and 3 times a month, and focus primarily on writing, German history and travel, as well as films and books. I will also introduce you to other authors in a variety of genres, so drop your email to stay up-to-date!