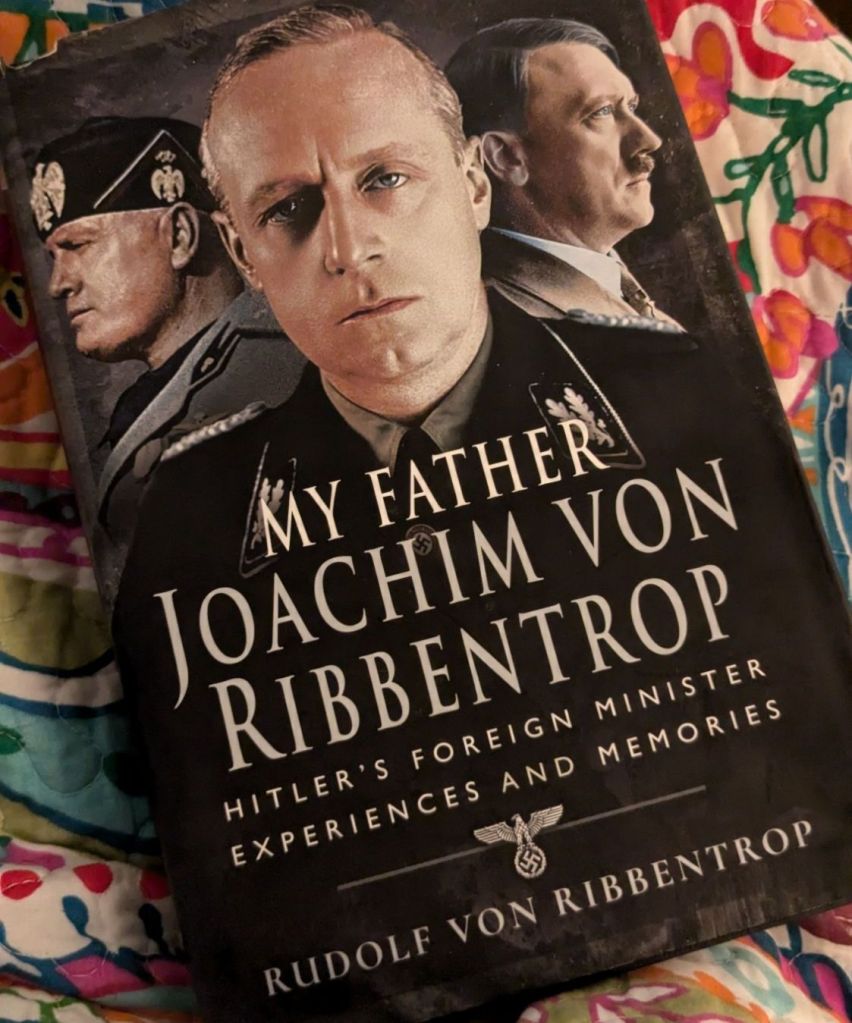

I was legitimately sad when this book ended, because in Rudolf von Ribbentrop, the son of the much-maligned German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, I found a kindred spirit. He is the author of this book, which is part biography, part memoir.

It is easily one of my top five reads for 2024.

As the eldest son of Joachim and Annelise von Ribbentrop, the author was entrusted with his parents’ deepest thoughts, and occasionally present during diplomatic functions. It qualified him to write such a book with a unique understanding of both his father and the times they lived through as a family.

One of the author’s favorite quotes was an old Chinese proverb:

If I wished to do you harm, I would wish you a famous father!

In spite of his connections, as a young man, Rudolf von Ribbentrop refused to simply rest on his father’s position. It was the principles on which he was raised, and not his famous father, that enabled him to become a respected officer in an elite tank unit. It was likewise the family tradition of tenacity (going back generations, their motto was “do not give up”) that allowed him to remain doggedly determined to do what had to be done, even when the war had turned against Germany, and during his 3-year imprisonment.

In the end, his sense of duty was to his country, and not its leader. To his men, and not the organization to which he belonged. To his family’s name, not to himself. (It is interesting that all the qualities mentioned above could be applied to both father and son.)

Though he was clearly interested in giving a defense of his father, Rudolf von Ribbentrop also confessed to the faults he perceived in the man. His father was much-maligned, not just in the course of history, but by his own countrymen and those within the National Socialist regime. However, the younger Ribbentrop takes time to include instances where people gave high praise for his father. My favorite:

“Ribbentrop never let anybody down!”

Karlfried Count Duerkheim, a ‘non-Aryan’ who worked under Ribbentrop. In 1941, Ribbentrop sent him on mission to Japan, to protect him from the increasing anti-Semitism in Germany.

When I say Rudolf von Ribbentrop is a kindred spirit, it is because he treats the entirety of the times in which he was embroiled with a true and balanced approach. He clearly spent years of his life researching and working to piece this book together, doing work that so many historians, even German ones, were unwilling to do (and still are). He refuses to keep to the “narrative,” but instead calls out the narrative when necessary. He indicts the victorious Allies, but just was willingly called out the faults of the National Socialist regime and its leaders.

He makes valuable and important arguments against the implication of the larger German population in the crimes of a few hundred “in the know” at the top of the Third Reich. By the end of the book, you can sense his heart. Below, he is not talking about National Socialist ideology, or Hitler. He is talking about his love for his nation, and his people.

“…to submit body and soul to an idea – for instance to a God or the idea of one’s fatherland or something held by each to be of value to which the whole person is duty bound to dedicate their self … Nothing alters this ascertainment, even when a subsequent somewhat melancholy realization dawns upon one that is evidently no longer that country of mine to which I had given my commitment; a country in which those citizens are defamed as ‘murderers’ who are or were at any rate ready to give up their life for their homeland. They can not, or could not, in general judge the politics, let alone influence them, but they were prepared for the eventuality of having to sacrifice their life for their country.”

Throughout the book, I kept wishing that Rudolf von Ribbentrop had been my history teacher, or at the very least, that he had written more books. I was grateful that he included some insight into his own war experience as a low-ranking officer in the tank corps of the Waffen-SS. He gives special attention to Kharkov and Kursk, particularly the famous tank battle at Prokhorovka, something I wish I could have given more attention to in my book The Rubicon.

My only complaint about this book is that occasionally, I found the writing style to be confusing and convoluted. It may have been an issue with the translation. Something that seemed overly complex in English may have made perfect sense in German.

Readers will also want to keep a dictionary or phone handy. Ribbentrop, or possibly the translator, or both–uses a lot of ten-dollar words.

Though it is a lengthy and detailed read, I consider this book a must-read for anyone who is truly interested in learning about “the German perspective.” As I stated above, the author gives important and reasoned explanations for what was going on on Germany’s foreign policy front (as well as, to a large degree, inside Germany) between the years 1933 and 1945.

Don’t ask me why certain figures out of history grab my attention. The reasons are probably as varied as the individuals themselves. After reading Mission at Nuremberg by Tim Townsend, I wanted to get to know this man who was convicted at the first of the Nuremberg trials, and was the first to be hung on October 16, 1946 (since Hermann Goering had committed suicide).

I feel like this post can only scratch the surface. If these observations intrigue you, take the time to read the book in its entirety.

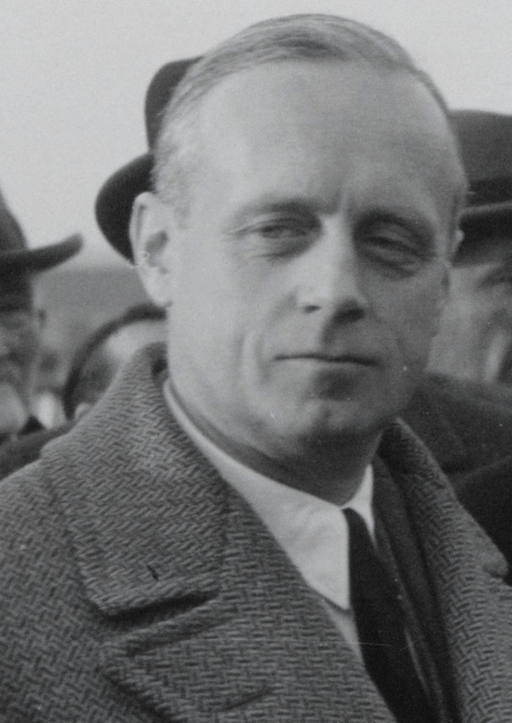

фонд ЦГАКФД, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

I think some of these go without saying, but I will start with a few high-level takeaways:

- We can’t simply label everyone who worked for the National Socialist regime a “Nazi.”

- History has slandered Joachim von Ribbentrop as a “yes man” to Hitler. He was anything but.

- Loyalty was one of his best qualities.

- Nice guys finish last.

Prior to civilian life he had served in the First World War as an officer–although he knew that he was not called to the soldiering life as a career. After the war, he lived in Canada and America for a time, and was fluent in French and English. He could speak the latter without an accent.

Though he married into the Henkell family, he became an entrepreneur and a successful wine and liquor merchant in his own right, for example, distributing England’s Johnny Walker whiskey throughout Germany.

He was never a convinced National Socialist. If anything, he could have easily bowed out of politics at any time, or have never gotten involved in the first place. What led him to become first a supporter of Hitler and then part of the National Socialist regime was the firm conviction that Germany only had two choices: Hitler or Communism.

The word “Communism” circulates today as a fuzzy concept. Back then, the memory of the Communist takeover in Russia was very fresh. Bloody battles, massive purges and man-made famines took place in Russian-controlled areas throughout the interwar years.

By the end of the First World War, Bolshevism was also beginning to make inroads into Central Europe. Whether it was the legitimate terror caused by having a machine gun planted in the middle of a city block, the terror spread by rumors and the media, or street battles between rival militias, people were desperate for stability, while at the same time paralyzed by the fear that that stability may come through Russian conditions.

Many historians and commentators feel they have the standing to judge whether this was truly a risk. To them, the author says:

“Whoever did not live through it cannot imagine to what extent the catastrophe of 1918 and the desperate situation of the Reich … the ambiance was propitious to accept extraordinary measures and circumstances.”

This truly resonates with me because some historians seem to want to belittle the role these circumstances played in the rise of Hitler. As if people had a choice and simply made the wrong one.

They absolutely cannot judge, because they were not there.

Likewise, when referring to the latter half of Hitler’s reign, and why people allowed him to remain after he had lost credibility and plunged them into another bloody war, the author states:

“To remove Hitler would set the seal on defeat in the form postulated by Roosevelt and Churchill of ‘unconditional surrender’, with the incursion of the Soviets into Central Europe. Who today can imagine the desperate predicament faced in those days by many good Germans: Their own country in a life-or-death battle, led by a dictator and his regime which did not appear acceptable to them?”

What is most unfortunate to me is the fact that once a statement is made repeatedly, it becomes truth. This is the case with a lot of the accusations of historians. They borrow from each other rather than investigating the truth. For example, it has gone down in history that Ribbentrop lied to Hitler about England’s readiness to go to war. As if the Foreign Minister told Hitler that England was not interested in another war, and was certainly not in a position to do so.

Rudolf von Ribbentrop describes with utmost certainty, and backs it up with documentation that this is not what his father said; rather, his father warned Hitler that England was indeed capable of, and ready to go to war to defend her interests. The younger Ribbentrop very carefully gives citations for these and other bold arguments. As I said before, he clearly dedicated many years of his life to this research.

Ribbentrop also defends his father’s personal choice to remain a part of the Regime, even as things went from bad to worse and Hitler became increasingly inflexible: “Father would on no account become a rat [abandoning a sinking ship], and had not been born to be an assassin.”

Above, I mentioned that loyalty was one of Joachim von Ribbentrop’s best qualities. While he was no “yes man,” he did maintain a certain respect for and loyalty to Hitler. It is at this point that I will touch on things of faith a source of my interest in Ribbentrop. In the Bible we are commanded to honor our leaders. This command is given by men who lived under some of the most evil Emperors of Ancient Rome.

It is rare that a man can remain loyal to his convictions and at the same time loyal to his leader when the two are so diametrically opposed. Joachim von Ribbentrop seemed to have found that balance. He went head to head with Hitler, expressing his viewpoints, but did not push when it was clear Hitler had made up his mind. Further, Ribbentrop did not abandon ship when it was clear there was no longer any hope for Germany. It seems to me that he knew subconsciously that he needed to be there, to have the ear of Hitler as a voice of reason, when so many weren’t.

Ultimately, that may be what led me to my final bullet point above, which is said somewhat tongue in cheek, that “nice guys finish last.”

For all the bad press he’s gotten for over 90 years, Joachim von Ribbentrop strikes me as a cool headed, rational thinker. He had always–from the beginning–had utmost in his mind the goal of strengthening Germany’s uncomfortable position in the center of Europe, and to do so in an honorable way. He wanted to help facilitate peaceful agreements between Germany and Poland, Germany and the “Western Powers” (France and England), and finally, between Germany and the Soviet Union.

Ribbentrop would meet with very little success in these ventures. When Hitler determined to preemptively invade the Soviet Union, Ribbentrop urged against that course of action. Throughout the war in the East, he continually asked that Hitler allow him to seek peace with Russia.

Rudolf von Ribbentrop does not take the time to refute each and every calumny made against his father. He says himself that there are “hard political facts of long, great, and momentous effect.” There are a few instances in which he belabors the point, but he is much more interested in giving his account of a great many political events, from his own perspective, his father’s perspective, and the German perspective as a whole. The book provides a great view into the inner workings of the National Socialist regime and the unique nature of Hitler’s dictatorship.

Joachim von Ribbentrop was stuck between a rock and a hard place. He had morals and standards which other people in power either didn’t possess or they ignored them. He wouldn’t compromise, except in that, in order to guarantee that Bolshevism did not get the upper hand, which it certainly would have, he placed himself under Hitler. What followed in the twelve years of the Third Reich, along with its far-reaching aftermath, could not have been known.

I would not want to have been in his position. To have to deal with foreign diplomats with opposing and even hostile views. To know that so many of your own party didn’t approve of you, and to work under a dictator like Hitler. (As I mentioned earlier, Joachim von Ribbentrop did not subscribe to the worldview of National Socialism. He had an uphill battle at every turn, because his Fuehrer’s worldview was incompatible with all the other worldviews out there. Finding common ground for alliances was next to impossible.)

What Ribbentrop saw was not glory for Germany in an extended takeover of Europe and Russia. He saw a safe and balanced place for Germany amongst the other nations of Europe, balanced with the great Anglo-Saxon powers (The British Empire and the USA) in the West and Russia in the East.

The last time father and son spoke to each other as free men, the elder von Ribbentrop said twice, “It was a great opportunity for Germany.” As his son recounts, “Unspoken in the air was the sequel, ‘if I had been listened to!'”

United States Army Signal Corps photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As stated above, Rudolf von Ribbentrop is not afraid to make bold statements against the victorious powers. Regarding Nuremberg, he states that like the others, Joachim von Ribbentrop was “successfully prevented from declaring his motives at Nuremberg.”

The Allies gave themselves the right of the ‘law of nations’ to take the life of the Foreign Minister of their opponent, the basis for which was nothing other than the primitive right of the victor … To condemn Father for having conducted a war of aggression against Poland in the presence of Soviet judges, when the Soviet Union had also attacked Poland, blatantly proves the injustice of this so-called litigation.

Rudolf von Ribbentrop was an incredibly intelligent man who spent years patiently amassing well-documented information, processing it, and making his case. He did it well and I hope that I have done a modicum of justice to his efforts. History needs people who are willing to take on the whole story and call out the ways in which history has been falsified.

I’m not talking about revisionism, although if that is the way people want to think of it, so be it. We forget that there are real people’s lives involved. That Germany’s shame as a nation boils down to individual families that still deal with the pain of the past. Guilt for things they themselves were not even involved in, or alive to see.

I had a nice talk with an older man at Thanksgiving. He is a Polish-American, and he knows about my passion for my German heritage. Initially we chatted about the Second World War, and what it came down to for him (not specifically about the two of us, but about the way individuals of different people groups continue to hate each other) was that we who are alive now were not there. We were not involved. We need to move past those things. We owe it to each other to learn to communicate rather than put up walls and refuse to see from the other’s perspective. It was obvious he was thinking far beyond the Second World War. The concept could apply to any nation, people group, religion, political party, or simply between friends and family members.

This has been lengthy. If you’ve held on until the end, you deserve a round of applause! Please leave a comment below if something grabbed your attention.

If you want to be informed about the latest on the Aubrey Taylor Books Blog, sign up below. Posts happen between 1 and 3 times a month, and focus primarily on writing, German history and travel, as well as films and books. I will also introduce you to other authors in a variety of genres, so drop your email to stay up-to-date!