Why has it taken me so long to review one of Erich Maria Remarque’s books? He is my favorite author, hands down, and though I doubt we’d see eye to eye on certain things, I wish I could sit down with him over coffee and talk. And talk and talk and talk.

One of the reasons I am so riveted by Remarque’s work is that I am a sucker for strong, well-written characters. Remarque’s writing grabs you as if he were writing in “Deep POV” long before it became a thing. In Remarque’s books, I’ve lived in the trenches alongside Paul Bäumer in All Quiet on the Western Front, struggled through Ernst Burkholz’s return from the front in The Road Back, felt the pain of love and loss with Ernst Gräber in A Time to Love and a Time to Die, and experienced Robert Lohkamp’s slow-burn romance, and his struggle alongside the ailing Patricia in Three Comrades. I’ve also enjoyed a series of his short stories that were published in Colliers in the 1930s.

I really need to go back and reread All Quiet on the Western Front, but I am already reading at least three other WW1 books. So, I’ve chosen to review one of EMR books I read recently, Three Comrades. So far, honestly, it has moved me the most of all his books.

The story begins with Robert Lohkamp’s and his friendships with Köster and Lenz, two former comrades with whom he fought during the First World War. The three now work together at Köster’s car repair shop, along with a youthful fourth character named Jupp.

I savored these deep, supportive relationships, as well as Robert’s interactions with more peripheral characters whose presence lent both comic relief and pathos to one of Remarque’s typically tragic (but beautiful) stories. Even “the prostitutes” were well thought-out, individual characters with unique personalities. I found I sympathized with them in spite of their position in life… or perhaps due to it.

Early in the story, Robert meets a young woman named Patricia Hollmann, whom he considers to be altogether above him. He isn’t interested in love anyway–his rather jaded, nihilistic outlook has left him cynical about love and everything else. He is intrigued by her, though, and soon feels driven to spend time with her.

Maybe it’s because back in high school, I was the proverbial clingy girlfriend, but one of the things I noticed among these comrades was that the introduction of a woman into the mix did not throw their friendships off kilter.

In the long run, Robbie’s relationships are reinforced as he begins to realize that Pat is terminally ill. Rather than rejecting her or holding her at arms length, he suffers alongside her, and Köster and Lenz step up in ways only true comrades can.

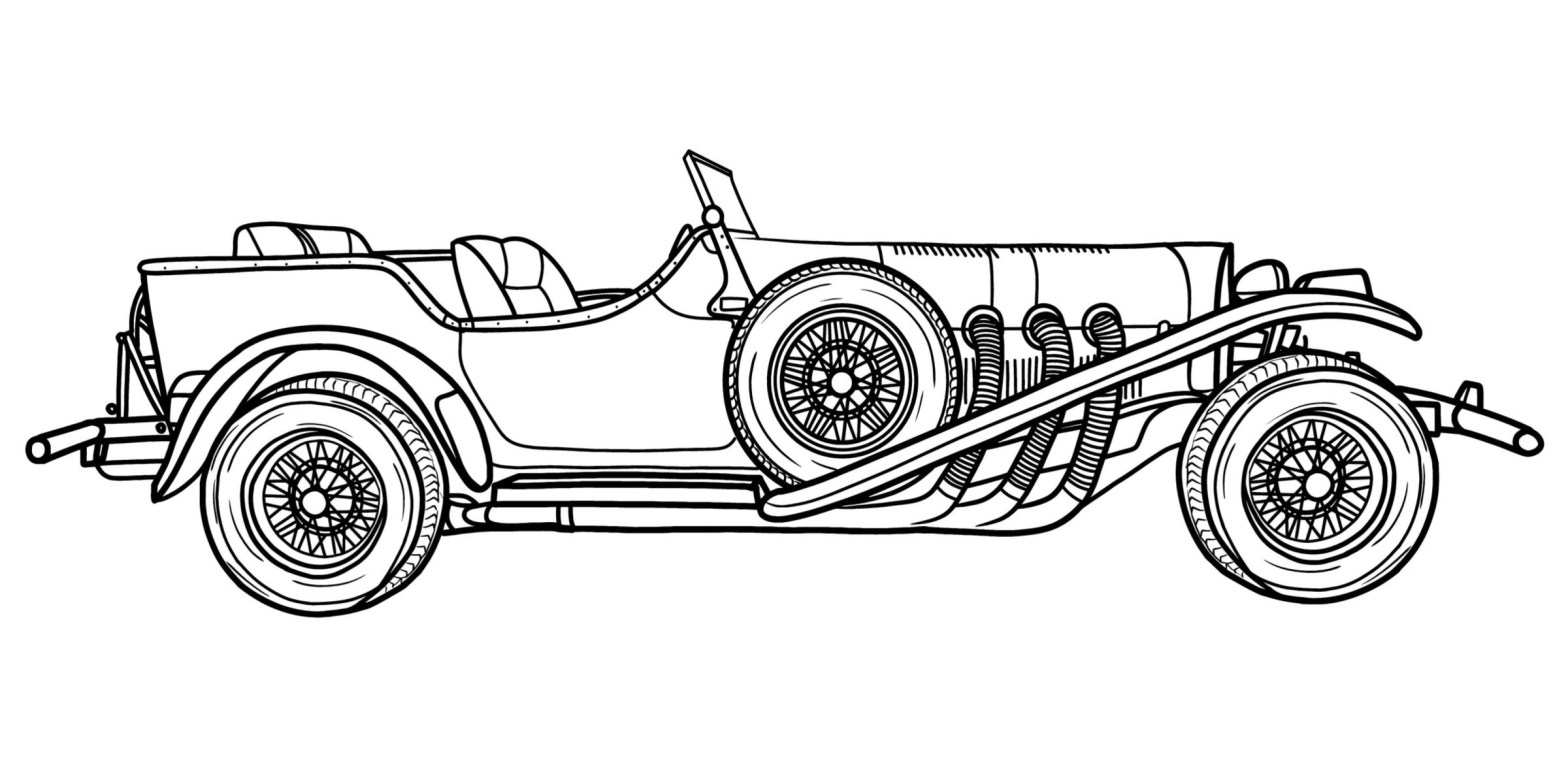

Aside from the human characters, there is Karl, the cobbled-together hot rod built in Köster’s shop and driven by the Three Comrades. “He” is not just a form of transportation; he is a car which, at first glance, elicits the ridicule of other drivers–but soon overtakes them on the track.

Remarque is a TRUE romantic. However, some people don’t like his stories because they are so typically German. His books are raw and heart-wrenching, which is why I love them. There are battles, prostitutes, broken marriages, illness, addiction, lying, death, and drinking. Lots of drinking. And, he does not provide the reader with the hoped-for “happily ever after.” These are all the things that show the truth and desperation of humanity.

Remarque’s books give readers a deep, insightful and honest picture of Germany in the first half of the 20th Century, in spite of the fact that he himself left in 1933 to escape National Socialism. He left by way of Switzerland, eventually moving to America. In 1938 he was stripped of his German citizenship, and in 1945 he told the New York Times that he no longer considered himself German:

“For I do not think in German nor feel German,

Erich Maria Remarque

nor talk German. Even when I dream it is about

America, and when I swear, it is in American.”

When I first heard this quote, I felt offense, because I am the exact opposite, having only discovered a love for my German heritage in the last four years. However, I think it is the very absence of any sort of connection to my heritage in the first 40 years of my life that has enabled me to love it so now.

My ancestors and I were also spared the worst years of Germany’s history.

The more I process the words above, the more I respect them. There is a reason Remarque felt the way he did. One need to look no further than the last few American presidential elections: major political changes can make you feel as if your own country is no longer yours–or, that your country is finally yours once again.

I strive to keep modern-day politics out of my writing, but hearing people say if a particular candidate was to win the election, they’d leave the country, makes me think of how Remarque must have felt in his day. Born in 1898, he’d grown up in Wilhelmine (Imperial) Germany, fought in the Great War, experienced the political chaos of the postwar years, and tasted the exciting cesspool that was “democratic” Weimar. Remarque had lived through four different “Germanys” in 35 years… and then the Third Reich began.

Many Germans were eager to escape. Remarque had the motivation as well as the means, so he did. In leaving Germany, he gifted America and the world with his stories, inspired by his experiences, and created a bridge between the Americans and the Germans who were, at the time, struggling to be perceived as something besides the enemy.

I can’t help but bring up my favorite actor, who is also a German expat. Thomas Kretschmann has been in such recent films as Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny and King Kong. You might also recognize his brief role in The Pianist, where he plays German captain Wilm Hosenfeld, but his filmography goes way back to the 1980’s. Someday I’ll review the German film Stalingrad, one of my all-time favorites.

Given how much I love Thomas Kretschmann’s acting, and how much I respect him for taking on so many difficult roles (people joke that he’s worn more German uniforms than the entire German General Staff during WWII), I was really shocked to read one of his quotes on IMDB. Without taking his words out of context, the phrase that got me was, “Germany sucks.” I had to process it, take time to consider his backstory (which included running for six hours straight to escape from East Germany), and the story of his people. What emerged was a greater understanding and sensitivity for him as an individual, not just as a celebrity.

I love Germany… maybe its America that I’m not grateful enough for, because both of these men, and many others including my ancestors and some dear friends, chose America over Germany and made it their home.

But I digress…

Three Comrades is set during the late 1920s and early 1930s. Germany had begun to experience a few relatively good years after the depths of their postwar desperation, though many people were still out of work and suffering. The world was headed into the Great Depression. Politics in Germany were becoming tumultuous again. After their initial failure, the National Socialist (“Nazi”) Party was on the rise once more. Communists battled Nationalists in the street. Political meetings also turned violent.

Three Comrades, along with Remarque’s short stories and The Road Back, gives the reader a good feel for what this tumultuous period of time was like. Historically, these years set the stage for much of what would happen later in German history, and that still affects Germany today (though most people don’t look back that far; they only see the Nazi period).

Sometimes I think that the tumult and instability of Germany’s past that draws me to it. The desperation and suffering of the people is something we don’t often consider, because there is still so much focus on their national sins.

Finally, Three Comrades touched me on a personal level. I’ve written before about my struggles with chronic illness. I was having a bad couple of days when I first sat down to write this post (months ago now). Robbie’s care for Patricia was so tender, so devoted–which was so surprising given who he was at the start of the book. It is that sensitivity, that empathy, that I love to see in male characters. As a female who writes predominantly male characters, it is important for me to observe how men see themselves, and how their brains work–and Remarque is one of my leading resources in that regard.

I have never failed to take note of how Remarque describes intimacy, because he speaks (through the man’s perspective) of the beauty of the woman. He is tactful and brief, but take note (sensitive readers) that intimacy is present. Though his characters are soldiers who have become hardened through battle, there still exists a tenderness that echoes the Biblical phrase, “It is not good for a man to be alone.”

When it comes to Remarque, I feel I could go on and on, but I have belabored this post long enough. I really hope you’ve enjoyed it and that if you haven’t picked up one of his books, you’ll give it this one a try. It’s a great choice because there are no gory battle scenes, and it has both comedy and romance. His war stories are perhaps a tougher sell for people who don’t like violence. If you’re uncomfortable with drinking or some mild swearing, well… his books may not be for you. But if you can overlook those things, I promise you an amazing history lesson, a heart-wrenching story, and unforgettable characters.

If you want to be informed about the latest on the Aubrey Taylor Books Blog, sign up below. Posts happen between 1 and 3 times a month, and focus primarily on writing, German history and travel, as well as films and books. I will also introduce you to other authors in a variety of genres, so drop your email to stay up-to-date!